Typically, I write about speech. But today I want to take a new look at the role of the listener in leadership communication. To borrow a page from Apple, you have to learn to “Listen Different.”

Of course, it is incumbent upon you as the speaker to present your information in a way that will make sense to the listener of the moment, and the ability to adapt your speaking style to fit the context is generally viewed as a strong leadership skill. But that’s only half the story.

Not everyone is going to be good at adapting their speech to fit your expectations for what good communication sounds like. As a result, if you don’t learn to listen differently, you are at risk for missing some of the most valuable information, simply because you don’t see the diamond through the coal dust.

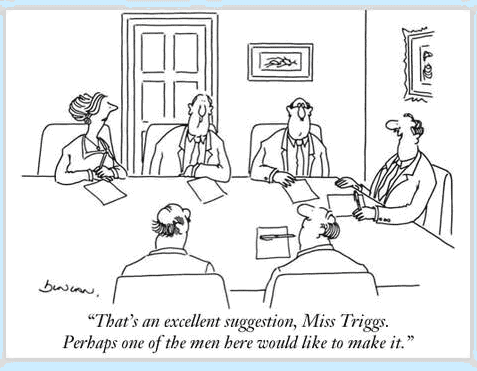

As an example, I work with a lot of women’s groups, and one of the most common frustrations I hear is when a woman makes a comment in a meeting, which gets glossed over, and then five minutes later one of the men at the table says almost the exact same thing, but he is praised for the contribution. The following cartoon illustrates the sentiment.

But gender-bias issues aside, it begs the question of why this is such a commonly shared experience, and what to do about it, because the underlying principle stands for everyone – men and women. The truth is that the responsibility for change is shared by everyone at the table. Here’s why:

One reason that some people may feel like they don’t get heard is because the way they frame their ideas makes it subconsciously harder for the listener to register what they’ve said. For example, rather than state an idea like, “We haven’t tried X yet; let’s take a look at that option,” they say something like “What about X? Should we look at that? Would that work?”

The challenge is that many listeners don’t understand the nature of what they’re really hearing, and need to recognize the speaker’s intent. At their core, both of the above examples have the same underlying purpose and meaning (what linguists refer to as the “illocutionary force”): making a suggestion. But on the surface (the “locutionary force”), the former’s grammar is confidently asserting a recommendation, whereas the latter is literally asking questions that seek validation from the others regarding the nature of the idea.

Mind you, there is a time and a place for each approach. The former is typically more effective in contexts where strength, assertiveness and confidence are valued; in that case, the indirect style may fall on deaf ears, despite the inherent value of the suggestion. The latter will likely work better in groups who appreciate subtlety and a more collaborative approach that endeavors to show respect to group consensus, in which case the more assertive style can be dismissed as abrasive and unwelcome, regardless of how the speaker thought he or she came across.

If you’ve ever felt like Miss Triggs – that your message wasn’t heard, or was not received as intended – you might have framed your comment using the dis-preferred style for that group. While no group is going to use one style all the time, and most groups will claim to recognize both, the fact is that on a subconscious level, we tend to hear, process and respond to them differently.

That is, our default listening style tends to register them differently, which is why it’s important to go into conversations with the goal of listening more intently to identify each speaker’s content and intent. This is where the meeting facilitator and other participants in a discussion might miss the boat.

When listening, make sure you’re truly present when someone is speaking, because we first process tone and instinctive feeling before we process actual meaning. So, for example, while you’re pondering your own solutions for a problem, your brain might subconsciously register “someone is asking another question… I’m still working on answering my own, no time for another one now”, at which point you miss a great suggestion. Check your assumptions at the door, so that before your brain dismisses something as incorrect or unimportant, you take a second look to make sure you’re not missing something in the process.

And most importantly, if you are a participant in a discussion and you do hear the value in someone’s contribution but believe the convener or group has missed it, or if “Ms./Mr. Triggs” makes a comment that gets praise only when reiterated by someone else, it is then your responsibility to gently draw it to everyone’s attention: “Yes, Pat, I think you’re reinforcing what Chris said a moment ago about…” Passive listening and lack of proactive participation are not qualities of successful leadership.

It may be frustrating to feel like you need to work harder at listening, that people should just “speak clearly,” but as the saying goes, “the devil is in the details.” In the end, if you really want to lead, true leadership communication skills go beyond effective speaking. Whether you’re talking to a family member, employee, client or vendor, communication is a two-way street, so learn to listen different.