Everyone has needs; some of them are just more intuitive than others.

Ever ask yourself, “Why do I always do that?” If so, read on.

Most of us are familiar with Abraham Maslow’s original hierarchy of needs, which dates all the way back to 1943, ranging from physiological needs at the bottom (e.g. food, water, shelter), moving upwards through safety needs (employment/money, personal security), to self-efficacy at the top, i.e. (I’ll borrow a slogan from the Army here) the ability to “be all that you can be.”

Less well known is Tony Robbins’ model of the six human needs, but boy does it do a lot to explain human behavior.

At the foundation are two oddly contradictory needs:

- Certainty (i.e. security and – ahem — control)

- Variety (i.e. “uncertainty”)

Then there are two needs that address how we relate to others:

- Significance (feeling important, needed, special)

- Love and connection (platonic or romantic closeness, union)

And at the top are two more “spiritual” needs:

- The need for growth (personal or professional)

- The need for contribution (wanting to serve others regardless of personal benefit)

The biggest difference is that for the most part, Maslow’s needs are in logical order: i.e. if you don’t know where your next meal will come from (level 1), you’re not likely to be concerned at the moment with improving your social status (level 5).

But at any given moment, our driving force could be any one of Robbins’ needs.

Think about it: most of us are probably pretty secure in our homes and careers, and like to volunteer and “pay it forward,” which would be at the top of the hierarchy.

Nevertheless, have you ever succumbed to self-sabotaging actions? Maybe something like:

- Procrastinating and “accidentally” missing deadlines for job applications or proposals

- Eating half(?) a container of ice cream when you’ve been working hard to get healthier and lose weight

- Picking a fight or breaking up with someone when everything has been going fine

- Spending money on “retail therapy” when you know you’re trying to save for a mortgage down payment or to get out of debt

- Setting unattainable goals… or not bothering to set any at all

If so, at that moment, your driving force is the need for certainty.

When we’re afraid of the goal being too hard, the risk being too great, or failing to live up to expectations (our own or other people’s), we grasp at the opportunity to control something, even if it means creating the exact opposite of what we actually want.

The problem is that if there’s one thing that’s constant in life, it’s change, and even good change brings an element of risk.

That’s why the announcement of a major change has to be handled so carefully – so as not to trigger everyone’s fundamental need for safety and security (a-la Maslow) or certainty (a-la Robbins) and result in widespread panic.

How do you introduce change to your team? To your family? To your relationships?

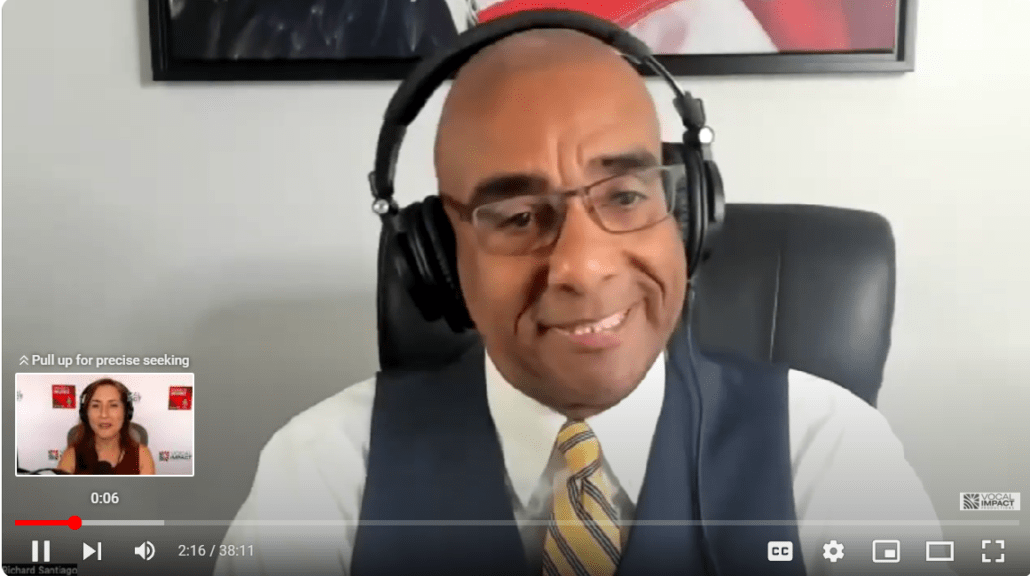

Want an example of announcing and managing massive change on a global scale? Look no further than this week’s episode of Speaking to Influence.

In honor of kicking off Hispanic Heritage Month, my guest, Dr. Richard Santiago, CFO (and retired lt. colonel) of the U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM), shares how he had to become an agent of change in order to implement institution-wide digital transformation that could not afford to fail across more than one hundred locations around the world.

In our conversation, Rich dives into how he:

- Developed a change management framework

- Communicated his role to all key stakeholder groups

- Built coalitions internally and externally

- Centralized problem solving

- Surrounded himself with subject matter experts

- And gave his people even more autonomy

All to ensure the success of the mission.

Listen to the full conversation here or watch the video on YouTube here.

While stress is a part of every change, and just about every job to one extent or another, a crucial distinction to identify is whether it is temporary or chronic, and whether it’s something we can reduce for ourselves, or is a systemic part of the institutional structure and culture.

In other words: Is the stress we’re feeling generic “burnout,” or more deeply, are we actually experiencing “Moral Injury”?

That’s exactly what Dr. Jennie Byrne, MD PhD and I discussed on Friday’s LinkedIn Live conversation.

And trust me, even if you missed the live event, you can’t afford to miss the replay, which you can find here.